Nicole Acero

This summer, for seventeen days, the whole world will unite as we set our eyes on Rio de Janeiro, Brazil to watch the 2016 Olympic Games. Not only is Rio de Janeiro hosting this year’s Games, the country is also the host of the Aedes mosquito, which carries the Zika virus. As thousands of people from around the world flock to Rio, they will be putting themselves at risk of contracting the virus or carrying it back to their home countries. Is a gold medal worth the risk of a worldwide epidemic?

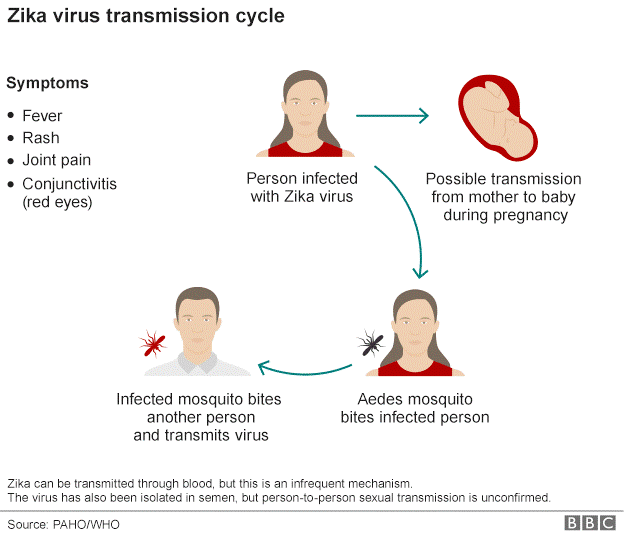

While Zika is initially transmitted through the Aedes mosquito, carriers can transmit the virus sexually, through blood, and if pregnant, to a fetus. Currently, no vaccine or cure for the virus exists, thus the only form of protection is to avoid getting bitten by the mosquito. Authorities argue that since the Games will be held in August, during Brazil’s winter, there will be few mosquitoes. However, temperatures in Brazil will still range between 64° F and 75° F, an ideal temperature for the mosquitos to thrive (Vox 2016).

If one contracts the disease, symptoms include fever, rashes, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (CDC 2016). Although these symptoms are mild and last only a few days, 20% of those with the virus are asymptomatic (Altman 2016). Those who are unaware they are infected can accidentally spread the disease to others. Furthermore, the inability to detect the disease makes surveillance and containment difficult. Meanwhile, the Games draw thousands of tourists and athletes. Many travelers engage in casual sex and can transmit the disease if unprotected. Tourists can also unknowingly bring the disease back home by spreading it to their sexual partners or to native mosquitoes, who will transmit it locally.

Fortunately, Zika’s effects are mild for adults who contract the disease. Treatment includes resting, drinking fluids, and taking acetaminophen. Unfortunately, for a fetus who contracts Zika, the effects are more permanent and the treatment costlier. A fetus whose mother contracts Zika can be born with microcephaly, a birth defect in which the size of a baby’s head is smaller than expected for the child’s age and sex. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Zika has been found in the brain tissue of fetuses who died of microcephaly and in the placental tissue of early miscarriages, providing evidence that Zika and microcephaly are linked (Martines et. al. 2016). Fortunately, women with the disease can still have a healthy child after recovering from Zika. Infectious disease specialist Dr. Gounder suggests waiting at least one month after recovering from the virus before trying to get pregnant (Wahl 2016). Despite this fact, Brazil has seen a rise in microcephaly from 150 cases a year to 5,079 suspected cases since October, which parallels the rise of Zika (Welch 2016). If the disease were to become a worldwide epidemic, countless unborn babies will be at risk of developing microcephaly.

The Brazilian government, International Olympic Committee, and World Health Organization are working together to further suppress fears and take action against Zika. Brazil has launched an effort to fumigate Rio, where most of the events will take place, both outdoors and indoors (Vox 2016). Researchers are also experimenting with ways to control the mosquito population by deploying genetically modified mosquitos and introducing Wolbachia, a bacterium that prevents disease transmission, into the mosquito population (Douglas). Health workers have also recommended that Brazilians check and clean their properties at least once a week, since a hatched Aedes mosquito egg requires seven to ten days to develop to adulthood. The Brazilian government has also dispatched 220,000 troops across the country to hand out leaflets which inform citizens on how to combat the virus (Hinde 2016). From these reports, Brazil is taking the necessary precautions for the Olympics.

While these measures are reassuring, they may not be enough to prevent the disease from spreading. Soccer games are planned to be held in cities outside Rio which have higher rates of mosquito-borne viruses (Wahl 2016). Citizens who live around Rio have claimed they see no evidence of the government’s efforts. According to Luiz Claudio Nascimento, a member of Carnaval’s cleaning crew, “We don’t do special cleaning for Zika. As far as we have been told, it is not so serious” (Hinde 2016). Moreover, many citizens have expressed a lack of faith in Brazil’s president, Dilma Rousseff, to take care of the situation since she has been accused of involvement in a bribery scandal and is facing potential impeachment. Additionally, despite the serious consequences of contracting Zika for pregnant women and their babies, the World Health Organization has not banned pregnant women from traveling to affected regions.

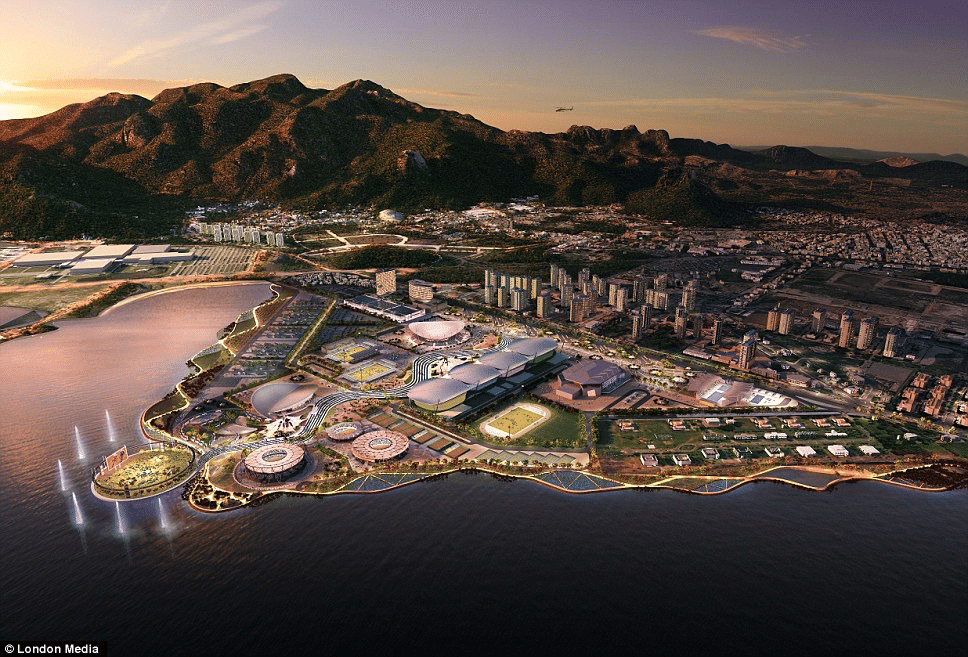

As with most public health issues, there is a political overtone when it comes to dealing with the Zika virus. The Brazilian government and countless investors have a large economic stake in the Olympics. In the midst of a crashing economy, scrutinized government, and embarrassment from losing the World Cup on home soil, Brazil is depending on the success of the Olympics to lure investors and earn back the world’s confidence. Eike Batista, former richest man in Brazil, was a major contributor in Brazil’s bid to host the Olympics, and foresaw the growth in tourism of Brazil as a result of his investments (Acero 2016). Edward Acero, an architect, was hired for the renovation of Batista’s Gloria Palace Hotel in Rio de Janeiro (Acero 2016). In an interview, Mr. Acero portrayed a first hand account of the immense amount of construction and development on new stadiums, the Olympic village, and new hotels or resorts in preparation for the Games. Mr. Acero recalls “meeting a lot of people leaving their current positions to work for firms that were doing something for the Olympics or World Cup.” From Mr. Acero’s economic perspective, “Canceling the Olympics would do more harm than good, especially when so much money has already been invested” (Acero 2016).

Money has been a major motivator when it comes to handling Zika. Suspiciously, despite past outbreaks of Zika, organizations are only now mobilizing against the disease. Since previous outbreaks have occurred in impoverished regions, a vaccine or cure for Zika was not considered a good investment. Capitalism has assigned people a monetary value, often blinding us from the fact that every life is a worthwhile investment. The World Health Organization only declared Zika an international public health emergency on February 1, 2016. This label puts the virus in the same category as Ebola, though it is not known to be as fatal (BBC 2016). The emergency signals the seriousness of the situation and offers countries who are experiencing outbreaks, such as Brazil, the tools needed to fight it (i.e. funding from governments and nonprofits around the world).

The Olympics-Zika scandal has shown us firsthand how politics and economics shape public health decisions. With billions of dollars at stake, cancelling or postponing the Olympics seems to be impossible; however, society must remember that people’s health and lives are at stake. Akin to Hunger Game novels and other dystopian literature, people must be wary of abusive political powers and address the social inequalities and poverty plaguing society. This summer, world leaders need to make a choice: economic catastrophe or worldwide epidemic? Which would you choose?